My cart

Your shopping cart is empty

The existence of precious stones and minerals has been known for ages. Their use in jewelry and art has been known since ancient times, and their beauty continues to amaze us to this day. Much has been and is being written about these earthly treasures, but very few writings have survived from Antiquity where we can understand more about how they were perceived and valued thousands of years ago.

In this article, we are writing about one such book, which, apart from being a work of art itself, also contains extremely valuable information for scientists, which gives us an idea of an era completely different from the one we live in today.

Until the 16th century, minerals and precious stones were described in the so-called lapidaries. A lapidary is an ancient document in which the author described the various properties and some important characteristics of minerals. The earliest such document that still exists today is part of a monumental 1st century AD encyclopedia called Naturalis Historia (History of Nature) written by Pliny the Elder. Most lapidaries are written in prose, but there are some that are in verse form. They influenced scientific thought in the Middle Ages and are a rich source of knowledge by which students and historians studying the period get inspired.

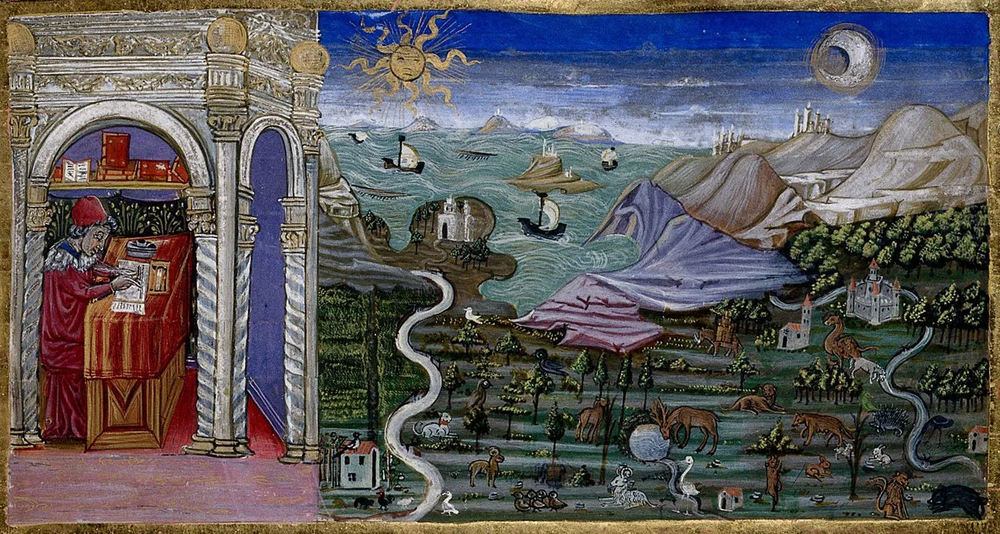

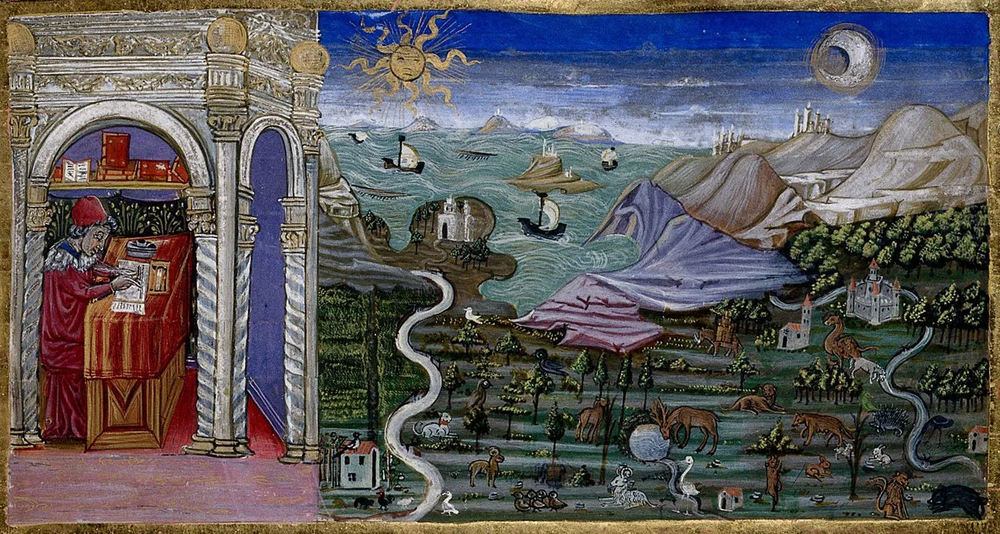

page from Naturalis Historia

photo: https://oddsalon.com

The Naturalis Historia is one of the world's earliest encyclopedias and is an impressive work that includes writings on subjects as diverse as art, astronomy, and even magic. It was published circa 77 AD and since then it began to spread throughout Europe. It is also one of the first works to be printed after the invention of the Gutenberg printing press in 1440.

Since the size of this work does not allow for a more in-depth examination within the scope of this article, we will focus only on the topic of precious stones. Naturalis Historia is Pliny the Elder's most famous work, a comprehensive encyclopedia of the natural world. This ancient text is also the longest continuous writing to survive from the Roman Empire and its popularity and circulation during the Middle Ages has kept it intact to this day.

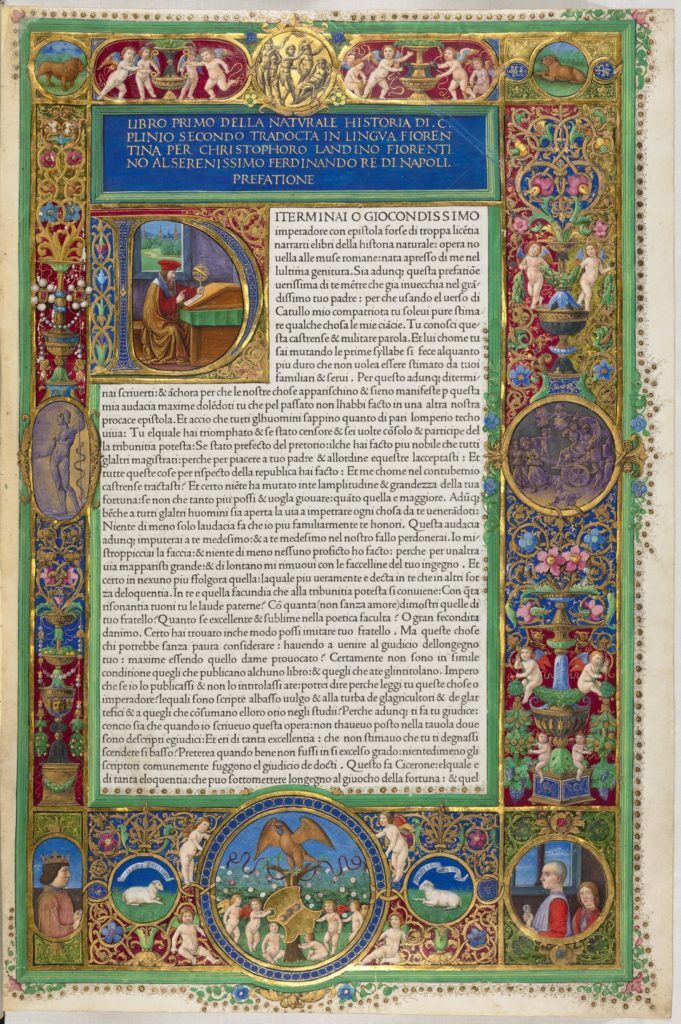

a copy of the encyclopedia

photo: https://oddsalon.com/

Gaius Plinio II, also known as Pliny the Elder, was born into a wealthy family in Como, Northern Italy in 23 AD. He was a Roman senator, writer, philosopher, and high-ranking military commander. Of him, his nephew Pliny the Younger wrote in one of his letters: "Happy is he, in my opinion, to whom the gods have given the power either to do something worth witnessing or to write something worth reading, and the happiest of all is he who is capable of both. Such a man was my uncle…”

portrait of Pliny the Elder by Sheila Terry

photo: https://sciencephotogallery.com/

Unfortunately, the death of this Roman naturalist is tragic. Pliny died in the devastating eruption of Mount Vesuvius on August 24 79 AD. Pliny the Younger also mentions how his uncle's natural curiosity about meteorological events, along with his desire to help others, dragged him into danger. It was his interest in natural phenomena that led him to approaching the erupting volcano by boat. Unfortunately, he never returned home and was subsequently discovered lying on the shore, having died of smoke inhalation.

Naturalis Historia is divided into 37 books, and in the introduction Pliny says that no other Roman author had begun such a project, and no Greek (Hellenic) subsequently had treated the work lighthandedly. And indeed, it is an impressive endeavor that has stood the test of time. To understand the dedication of the authors to the arts during those years, we only need to look in detail at this initial at the beginning of one of the pages, which depicts a stylized element, part of the zodiac:

decorative M letter

photo: mediastorehouse

This edition, edited by Giovanni Andrea, Bishop of Alleria, was published by Nicolas Jensen in 1472, only two years after the latter had established his printing house in Venice. In fact, this is not the only copy that Jensen printed until 1476 - a total of 1025 copies were printed. The book measures 29 cm wide, 40 m long and 9 cm high, and includes 716 pages, and the binding is made of calf leather.

Books 33 to 37 deal with topics related to mining and mineralogy, as well as working with precious metals (gold and silver). Pliny describes the various metals such as copper, mercury, lead, and aluminum, as well as their alloys. In addition to the factual work, the author adds his personal commentary as a philosopher.

In this part in particular, Pliny criticizes people's greed for the yellow metal and considers it absurd to use it to make coins. According to him, gold has unique qualities that allow it to be made into much finer and more exquisite objects of art. And about precious stones he says that they are so amazing that it is "blasphemous" to use them for engraving.

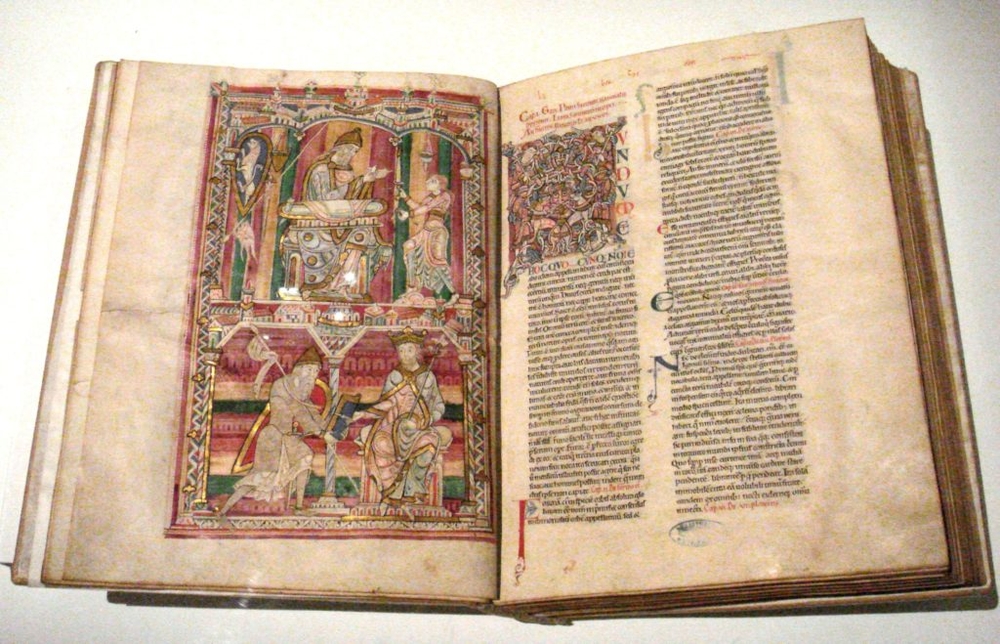

detail of illustration

photo: https://oddsalon.com/

In the last two books, Pliny describes various minerals, based on the works of Theophrastus and other ancient writers. The author graces us with a captivating description of the beauty of precious stones: "To many a single precious stone can present an incomparable and perfect view of Nature." Besides admiring the magnificence of natural beauty, Pliny the Elder gives several examples of the varying degree of extravagance attributed to them.

It is a curious fact that General Pompey ordered the making of a chessboard in honor of Pliny's multiple military victories, which was approximately 1.20m long and 30cm wide, and the figures up to the last one were made with engraved precious stones. But, as you probably guessed, this work of art also sleeps its eternal sleep under the ruins of the ancient city. We can only imagine its grace and craftsmanship…

Miniature by Andrea da Firenze

photo: Britannica

The hardness of the diamond was known even then, and the book mentions that diamond dust was used by engravers to cut and polish other precious stones. Pliny notes that the counterfeiting of precious stones was not uncommon in the empire and adds that there was a test that could be used to verify their authenticity. The test consisted of scratching with a steel blade, which would leave a mark on the surface of fakes, unlike authentic gems. Pliny's knowledge here of the hardness of minerals, which precedes the Mohs scale by centuries, is impressive.

In the first chapter, Pliny tells us about the first use of a precious stone in jewelry, as it is related to the ancient Greek myth of Prometheus: according to the legend, the stone, which was found in the Caucasus, was worn by the hero, who encased it in iron and made it into a ring. Since then, the value of precious stones rose immeasurably, and some were considered so precious that "no human wealth could put a price on them."

Another legend tells of the Samosan tyrant Polycrates, who was so rich that he considered it sufficient atonement to sacrifice one of his precious stones. So he boarded his ship and sailed to the waves, where he threw his ring. According to the legend, a large fish swallowed the jewel, which, to a great surprise, returned to its owner once again when the fish was caught and cooked in the royal kitchen. The stone that formed part of Polycrates' ring is believed to be sardonyx, and in the time of Pliny the Elder it was still on display in the Temple of Concord in Rome.

Thanks to the curiosity, dexterity and consistent work of our ancestors, we posses the invaluable gift of knowledge that helps us understand the world around us. Despite the sometimes controversial information in Pliny's writings, and more specifically in his Naturalis Historia, these texts served as a ladder that researchers in subsequent centuries climbed, in order to build science as we know it today.

Pliny the Elder's encyclopedia is a work whose purpose transcends the individual existence of man, and although it was created so many centuries ago, we find in it the foundations of many modern methods and concepts in various fields of knowledge.